Insight / Blog

HiveBox Case Study: How lockers became essential to Chinese ecommerce

The numbers tell their own story. Founded in 2015, HiveBox has received over a billion dollars of investment and is valued at over $3 billion USD. The initial funding ($78 million) came from 5 of China’s biggest logistics businesses: SF Express, UDA Express, STO Express, ZTO Express and GLP (Global Logistic Properties.) In and of itself this list of founders is remarkable. To translate this into UK terms, it would be like DPD, Royal Mail, Amazon and Hermes joining forces to create a parcel locker brand – in other words, almost unthinkable. Interestingly, the collaboration didn’t last. All of the carrier shareholders other than SF Express divested their shares in 2018, leaving just SF Express as the primary shareholder. The others joined Cainiao – the logistics network of Alibaba.

Since its founding, HiveBox has swiftly grown both organically and through acquisition. In 2017, HiveBox acquired a business called CIMC E-Commerce & Logistics Technology for $123 million, adding 14,000 additional lockers (and an estimated 800,000 parcels daily) to their network, which at the time was around 60,000 locker banks.

By 2020, the network was up to 170,000 banks of lockers, making it the biggest player in China’s parcel locker market, which in total ran to 400,000 lockers. In May of that year, HiveBox announced that it was acquiring its biggest competitor in the space: state-owned China Post’s own locker system, which represented nearly 25% of the market with 94,000 locker installations. That put HiveBox’s market share up to 65%. In January 2021, HiveBox completed another round of financing, receiving $400 million USD in funding. Today HiveBox is by some distance the biggest parcel locker operator in the world – but its business is more than just the hardware.

HiveBox offers several types of locker installation, catering to different requirements, and not all are for parcel delivery. They also offer lockers which are designed to provide secure storage for sensitive files to businesses, for example. Also interesting are the marketing and advertisement services which HiveBox has built into its business.

Parcel services

HiveBox’s bread and butter is the parcel delivery service. Its 170,000-strong locker network processes over 9 million daily parcels. These parcels are either chosen to be delivered to lockers by consumers at the checkout online, or they are dropped into lockers when couriers aren’t able to facilitate home delivery, although this can be controversial, as we will see later.

Pickups are straightforward: shoppers receive a QR code to scan at the locker, which automatically opens the right door with their parcel inside. This is the same system that has become popular for parcel lockers right across the world.

HiveBox also offers consumers a membership program. Membership costs ¥5 for a month, or ¥12 for three months. The dollar value of those prices seems crazy – just 76 cents per month – but the comparison is not particularly apt, as prices and general cost of living are significantly lower across the board in China compared to the US.

As the diagram of parcel services shows, membership to HiveBox allows consumers to leave parcels in the locker for up to 7 days free of charge. Non-members have 18 hours to collect their parcel. After this cut off, they pay ¥0.5 every 12 hours the parcel is uncollected, up to ¥3. There are also members discounts for delivery to HiveBox locations, and access to promotional offers from retailers.

On the courier side, a courier registers with HiveBox and then pays a small fee per parcel left in the locker, which is charged depending on the size of the box. Shoppers can also order items for delivery directly from HiveBox’s WeChat account. Here, HiveBox posts daily offers from retailers to its followers.

Advertisement services

HiveBox lockers are designed to be used almost like billboards, with advertising appearing on the lockers themselves, as well as on the smart locker screen and throughout HiveBox’s WeChat account. Membership data and social account data is available to advertising partners to target particular demographics and customer segments, and they can offer deals to HiveBox members.

Meeting consumer demand

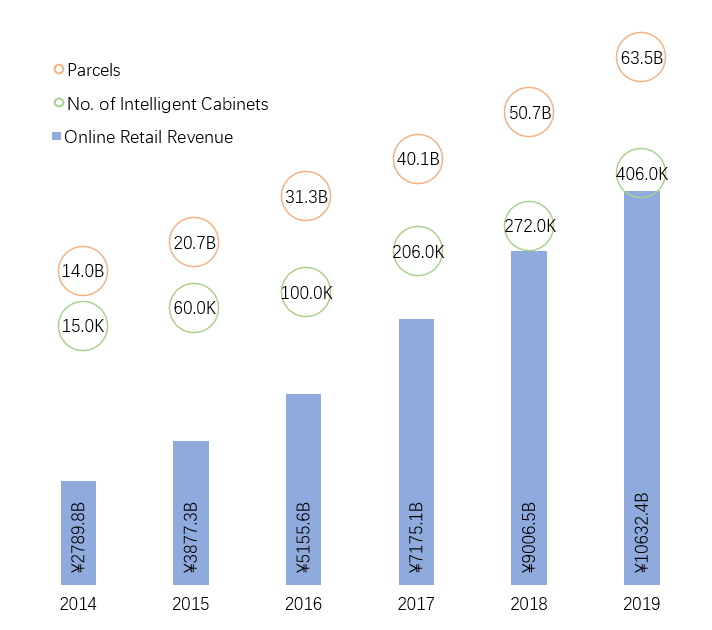

The graph shows the steady growth of ecommerce revenue, parcel volume and parcel locker installations (called intelligent cabinets in China.) As ecommerce parcel volumes have grown, so too have the challenges associated with delivery in China – failed deliveries, and consumer concerns with home delivery. Here in the UK, we don’t think twice about the fact that our delivery driver has our full name and home address, and will know if we’re not at home. In other places in the world, consumer confidence in the process is not at the same level as it is here, and so there’s a greater appreciation for the security of a locker solution.

In addition to what the consumer wants, it’s also obvious that carriers have every incentive to deliver as many parcels to lockers as possible. Consolidating their deliveries like this helps them to deal with the ridiculous volumes – expected to total 74 billion for 2020 – in a profitable and efficient way.

New shoppers coming online

The Chinese ecommerce market is increasingly driven by shoppers in so-called lower-tier cities, outside of their provincial capitals. Parcels delivered outside of the 31 provincial capital cities accounted for just under two thirds of the total volume in 2020, a significant increase from 50.8% in 2015. In the cities where these parcels are being delivered, last-mile infrastructure is typically less advanced than in the major cities. These cities are therefore a strategic priority for HiveBox’s future development. Currently, HiveBox is operating in 100 cities across China.

Government support

HiveBox was a beneficiary of the social distancing measures and behaviour changes brought about by COVID-19, with government departments emphasizing lockers as a way to reduce contact between delivery drivers and customers. The State Post Office said in a February 2020 press conference that it would seek to “actively promote [parcel lockers]” as a delivery option, which has helped drive increased consumer adoption of parcel lockers.

Margin struggles

China’s parcel delivery industry remains intensely competitive, and while volumes have grown rapidly, competition on price between delivery companies has shrunk profit margins. COVID-19 also resulted in fewer delivery personnel being available, which has intensified the pressure on carriers to find ways of consolidating deliveries to maximise the efficiency of their available workforce.

HiveBox has also had challenges with profitability, posting losses of $120 million (USD) in 2019 and further losing nearly $130 million in the first 3 quarters of 2020. Historically its revenue has been driven by the advertising noted above and the small fee couriers pay to use the locker. It has also been somewhat controversial in attempting to make up losses in May 2020 by initiating the model of charging for parcels left in the lockers. Initially this came without a grace period (the 18-hour parcel dwell time limit now in place) and users took to social media to display their anger – with some going as far as cutting power supplies to locker banks in their area.

Part of the frustration was that carriers would frequently drop parcels into lockers without the previous consent of the shopper – to then be charged on top of this was unsurprisingly unpopular with Chinese consumers. So what do consumers make of HiveBox?

Consumer opinion

In a survey of 38,550 Chinese ecommerce shoppers from May 2020, over 40% said they needed the service of HiveBox a lot, and just 18% said they had no need of it. These respondents tended to be single white-collar workers, living alone in economically developed provinces and cities. Over 90% of respondents reported shopping online more than once per month, 67.6% said they shopped online more than 5 times per month.

For this demographic, HiveBox is vitally useful, because they are more likely to not be at home during the day, which makes receiving home deliveries difficult. However, this also can limit the times at which they are able or willing to pick up a parcel. This insight was the impetus behind HiveBox extending the 12 hour grace period for which parcels can be left in the lockers without charge, from 12 hours to 18 hours.

Carrier practices

Part of the concern Chinese consumers have exhibited around lockers is that they aren’t always in control of their use, with couriers dropping parcels into lockers without being asked to and despite the recipient being at home. The rule is that a courier should call before diverting a parcel to a locker, but the efficiency of the locker and the massive volumes of parcels to be delivered incentivizes couriers to override the consumer’s wishes. This leaves them open to be reported, or for consumers to request re-delivery.

However, given the rate at which these reports actually get made and fines are issued, it’s still economical for couriers to default to parcel lockers – perhaps while noting which addresses are liable to report them for doing so, and ensuring parcels for these addresses are delivered to home.

Conclusion

In sum, HiveBox is a key part of the delivery ecosystem in China, with nearly 70% of the parcel locker market in its grasp and encouragement from government departments. It’s enthusiastically adopted by parcel carriers – perhaps overly enthusiastically – and many consumers appreciate the convenience of a locker delivery, although they’re largely unwilling to pay extra to use a locker. It is worth mentioning that while the locker network receives a great deal of interest, lockers deliver a smaller proportion of out-of-home deliveries in China than classic PUDO operations being run out of convenience stores and post offices. Equally important is that there remains a tension between consumers wanting home delivery and couriers who are willing to outright skip the home delivery attempt in favour of using lockers as a first resort. This might end up with new regulation or increased enforcement with tougher penalties for carriers, or carriers may increase the price of home delivery in order to make it economically viable for them to actually attempt all of these deliveries.

Whichever way that tension resolves, China is going to be the first country in the world where more than half of retail happens online by the end of 2021, and that maturity and market size makes it a vital source of data for the future of ecommerce globally. The fact that around 40% of Chinese ecommerce deliveries are out-of-home deliveries illustrates the importance of consolidation in the last mile as markets mature – a lesson that many other carriers around the world are learning quickly today.

Related articles

Return fees or free returns: why not both?

Debates between return fees or free returns miss the bigger picture: how to address the root issues of returns.

Lessons from a decade in the first and last mile

A decade as Doddle taught us some lessons - and Blue Yonder helps us see what will matter in the next decade.

Important lessons from Leaders in Logistics 2024

Leaders in Logistics 24 dived into AI & automation, sustainability, changing ecommerce behaviours, emerging consumer expectations & predicted what the next decade had in store.